... is re-posted from BrainPickings in its luminous entirety and with the fervent hope that readers will follow links to read the complete E.O. Wilson essay and other related articles revisiting C.P. Snow and Johan Lehrer .... and why art and science need each other. Follow the link in the footer to subscribe to weekly email Brain Pickings.

‘In the early stages of creation of both art and science, everything in the mind is a story.’

This month, legendary Harvard sociobiologist

E. O. Wilson — who once

famously said that “the elegance, we can fairly say the beauty, of any particular scientific generalization is measured by its simplicity relative to the number of phenomena it can explain” — penned a terrific

Harvard Magazine piece on

the origin of the arts. One of Wilson’s most urgent points is something we’ve already seen articulated by

C. P. Snow, who in 1959 lamented

a dangerous cultural dichotomy, and

Johan Lehrer, who spoke of a

“fourth culture of knowledge” — the need for bridging the sciences and the humanities. Wilson writes:

Since the fading of the original Enlightenment during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, stubborn impasse has existed in the consilience of the humanities and natural sciences. One way to break it is to collate the creative process and writing styles of literature and scientific research. This might not prove so difficult as it first seems. Innovators in both of two domains are basically dreamers and storytellers. In the early stages of creation of both art and science, everything in the mind is a story.

Wilson’s great talent is perhaps the gift of bridging the poetic with the scientific:

If ever there was a reason for bringing the humanities and science closer together, it is the need to understand the true nature of the human sensory world, as contrasted with that seen by the rest of life. But there is another, even more important reason to move toward consilience among the great branches of learning. Substantial evidence now exists that human social behavior arose genetically by multilevel evolution. If this interpretation is correct, and a growing number of evolutionary biologists and anthropologists believe it is, we can expect a continuing conflict between components of behavior favored by individual selection and those favored by group selection. Selection at the individual level tends to create competitiveness and selfish behavior among group members—in status, mating, and the securing of resources. In opposition, selection between groups tends to create selfless behavior, expressed in greater generosity and altruism, which in turn promote stronger cohesion and strength of the group as a whole.

But the most expansive beauty of Wilson’s essay lies in his articulation of art, at the heart of which is a sentiment common to the greatest definitions

of science and

of philosophy:

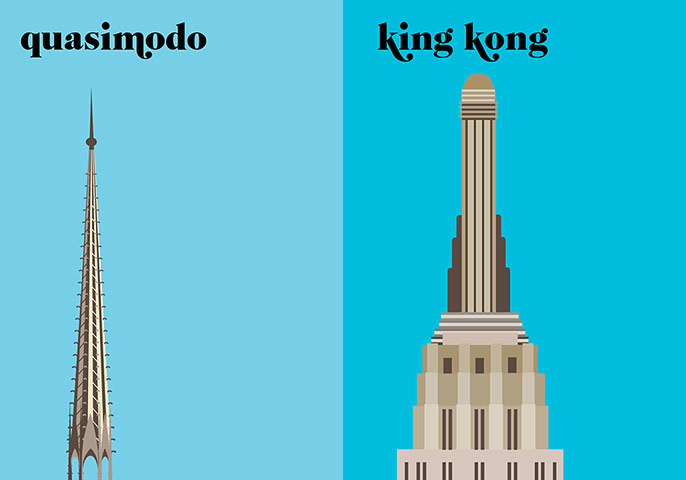

A quality of great art is its ability to guide attention from one of its parts to another in a manner that pleases, informs, and provokes.

Image by Desert Stars

This month, legendary Harvard sociobiologist E. O. Wilson — who once

This month, legendary Harvard sociobiologist E. O. Wilson — who once