|

|

If you missed last week's edition – Carl Sagan's reading list, Francis Bacon on studies, Vita Sackville-West's love letter to Virginia Woolf, and more – you can catch up right here. If you missed last week's edition – Carl Sagan's reading list, Francis Bacon on studies, Vita Sackville-West's love letter to Virginia Woolf, and more – you can catch up right here.

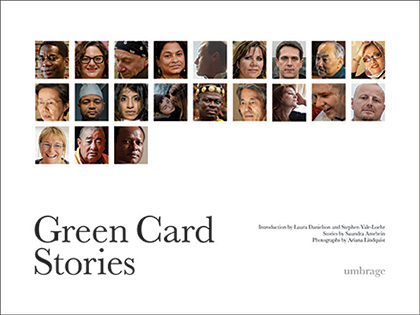

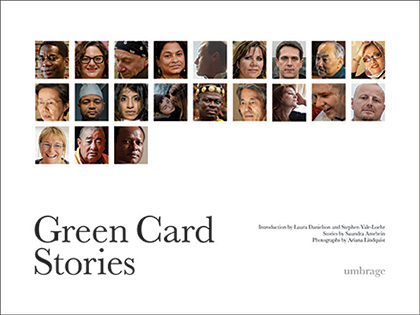

Poignant portrait of a system caught between hope and despair.

Having spent a good portion of my adult life wrangling the nine circles of my very own immigration hell, I feel a profound personal investment in the immigration debates that have swelled to particularly prodigious proportions around this year's election. Green Card Stories (public library) tells the heartening, and often dramatic, tales of fifty immigrants who recently attained their American residency or citizenship, accompanied by powerful profiles by journalist Saundra Amrhein and evocative portraits by documentary photographer Ariana Lindquist. Having spent a good portion of my adult life wrangling the nine circles of my very own immigration hell, I feel a profound personal investment in the immigration debates that have swelled to particularly prodigious proportions around this year's election. Green Card Stories (public library) tells the heartening, and often dramatic, tales of fifty immigrants who recently attained their American residency or citizenship, accompanied by powerful profiles by journalist Saundra Amrhein and evocative portraits by documentary photographer Ariana Lindquist.

Created in collaboration with acclaimed immigration lawyers and scholars Laura Danielson and Stephen Yale-Loehr, the project is in some ways a beautiful celebration of the triumph of hope embedded in the promise of the American Dream, and in others a poignant glimpse of a brutal system of struggle that can, if allowed to, eat away at one's deepest sense of dignity.

At its heart, however, the project aims straight for the bigoted misconceptions that immigrants are somehow less hard-working and passionate and full of potential than "real Americans," revealing instead the remarkable kaleidoscope of human life and purpose in those who have come to share their gifts with America. Humble yet proud, the voices in these stories – of artists, of scientists, of entrepreneurs, of dancers – bespeak a simple truth about place and personhood: Who you are and what you have to contribute to society cannot, nor should it, ever be reduced to or measured by a few legal check boxes, a set of biometric data, and a passport.

"I cannot bring together two ideas that you do not interpose yourself between them."

Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) might be as well-known for his literary legacy as he is for his tumultuous love life. At twenty-three, he fell for Mme. Berny, a woman nearly twice his age known as "la Dilecta," whose creative and intellectual influence on Balzac had a profound impact on shaping his budding voice. When the two split up in 1832, he entered a troubled relationship with the Marquise de Castries, whom he later portrayed rather unflatteringly in The Duchesse of Langeais. That year, he received a fan letter from Countess Ewelina Haska, a married Polish noblewoman to whom he came to refer to as "The Foreigner." They embarked upon an intense correspondence, which quickly escalated into a passionate bond, which lasted seventeen years. The two met twice – once in Switzerland the following year, and once in Vienna in 1835 – and the two vowed to marry once Ewelina's husband died. Though the Count passed away in 1842, Balzac's poor finances prevented the couple from marrying. In March of 1850, when he was already fatally ill, the two finally wed – five months before Balzac died in Paris. Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) might be as well-known for his literary legacy as he is for his tumultuous love life. At twenty-three, he fell for Mme. Berny, a woman nearly twice his age known as "la Dilecta," whose creative and intellectual influence on Balzac had a profound impact on shaping his budding voice. When the two split up in 1832, he entered a troubled relationship with the Marquise de Castries, whom he later portrayed rather unflatteringly in The Duchesse of Langeais. That year, he received a fan letter from Countess Ewelina Haska, a married Polish noblewoman to whom he came to refer to as "The Foreigner." They embarked upon an intense correspondence, which quickly escalated into a passionate bond, which lasted seventeen years. The two met twice – once in Switzerland the following year, and once in Vienna in 1835 – and the two vowed to marry once Ewelina's husband died. Though the Count passed away in 1842, Balzac's poor finances prevented the couple from marrying. In March of 1850, when he was already fatally ill, the two finally wed – five months before Balzac died in Paris.

June 1835 June 1835

MY BELOVED ANGEL,

I am nearly mad about you, as much as one can be mad: I cannot bring together two ideas that you do not interpose yourself between them. I can no longer think of nothing but you. In spite of myself, my imagination carries me to you. I grasp you, I kiss you, I caress you, a thousand of the most amorous caresses take possession of me. As for my heart, there you will always be – very much so. I have a delicious sense of you there. But my God, what is to become of me, if you have deprived me of my reason? This is a monomania which, this morning, terrifies me. I rise up every moment say to myself, 'Come, I am going there!' Then I sit down again, moved by the sense of my obligations. There is a frightful conflict. This is not a life. I have never before been like that. You have devoured everything. I feel foolish and happy as soon as I let myself think of you. I whirl round in a delicious dream in which in one instant I live a thousand years. What a horrible situation! Overcome with love, feeling love in every pore, living only for love, and seeing oneself consumed by griefs, and caught in a thousand spiders' threads. O, my darling Eva, you did not know it. I picked up your card. It is there before me, and I talked to you as if you were here. I see you, as I did yesterday, beautiful, astonishingly beautiful. Yesterday, during the whole evening, I said to myself 'She is mine!' Ah! The angels are not as happy in Paradise as I was yesterday!

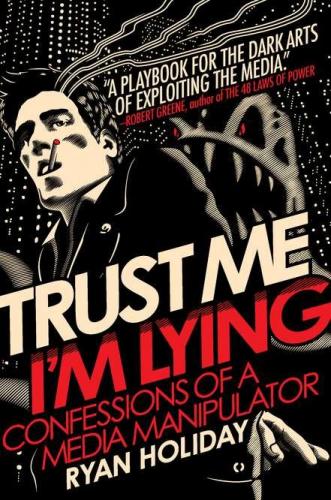

In devouring the newly released volume of Susan Sontag's diaries, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980 (public library), I came across two passages addressing something that concerns me daily – the reckless reduction of complex ideas into sticky soundbites and catchphrases, a practice that in the three decades since Sontag's writings has become not merely an accepted cultural standard, but a profitable business model in the "ideas economy." Under such commodification of thought, after a while, all these bite-sized ideas begin to sound, look and, eventually, act the same. In devouring the newly released volume of Susan Sontag's diaries, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980 (public library), I came across two passages addressing something that concerns me daily – the reckless reduction of complex ideas into sticky soundbites and catchphrases, a practice that in the three decades since Sontag's writings has become not merely an accepted cultural standard, but a profitable business model in the "ideas economy." Under such commodification of thought, after a while, all these bite-sized ideas begin to sound, look and, eventually, act the same.

In an entry dated April 26, 1980, Sontag offers a short but brilliant meditation on aphorisms – the ultimate soundbitification of thinking:

Aphorisms are rogue ideas. Aphorisms are rogue ideas.

Aphorism is aristocratic thinking: this is all the aristocrat is willing to tell you; he thinks you should get it fast, without spelling out all the details. Aphoristic thinking constructs thinking as an obstacle race: the reader is expected to get it fast, and move on. An aphorism is not an argument; it is too well-bred for that.

To write aphorisms is to assume a mask – a mask of scorn, of superiority. Which, in one great tradition, conceals (shapes) the aphorist's secret pursuit of spiritual salvation. The paradoxes of salvation. We know at the end, when the aphorist's amoral, light point-of-view self-destructs.

Then, ten days later, on May 6, she continues:

With the (1943) epigraph of Canetti. 'The great writers of aphorisms read as if they had all known each other very well.' With the (1943) epigraph of Canetti. 'The great writers of aphorisms read as if they had all known each other very well.'

One wonders why. Can it be that the literature of aphorisms teaches us the sameness of wisdom (as anthropology teaches us the diversity of culture)? The wisdom of pessimism. Or should we rather conclude that the form of the aphorism, of abbreviated or condensed or rogue thought, is a historically-colored voice which, when adopted, inevitably suggests certain attitudes; is the vehicle of a common thematics?

The traditional thematics of the aphorist: the hypocrisies of societies, the vanities of human wishes, the shallowness + deviousness of women; the sham of love; the pleasures (and necessity) of solitude; + the intricacies of one's own thought processes.

[…]

Aphoristic thinking is impatient thinking: by its very brevity or concentratedness, it presupposes a superior standard …

Modern macroeconomics traces many of its central tenets to the work of British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). Besides his seminal work on understanding the causes of business cycles and developing strategies for countering recessions and depressions, Keynes was also a champion of humanism and a sociocultural optimist at heart. Nowhere does this shine more brightly, and with more prescience, than in his 1930 essay, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (free PDF), in which Keynes sets out to "to disembarrass [himself] of short views and take wings into the future" by envisioning culture and society 100 years later, or in the near-present. His insights are, in retrospect, bittersweet – at once standing in stark contrast with the realities of the Occupy era and presenting a poignant reminder that our future is, indeed, still our choice. Modern macroeconomics traces many of its central tenets to the work of British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). Besides his seminal work on understanding the causes of business cycles and developing strategies for countering recessions and depressions, Keynes was also a champion of humanism and a sociocultural optimist at heart. Nowhere does this shine more brightly, and with more prescience, than in his 1930 essay, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (free PDF), in which Keynes sets out to "to disembarrass [himself] of short views and take wings into the future" by envisioning culture and society 100 years later, or in the near-present. His insights are, in retrospect, bittersweet – at once standing in stark contrast with the realities of the Occupy era and presenting a poignant reminder that our future is, indeed, still our choice.

Keynes speaks of "technological unemployment," driven by the emergence of new technologies that displace human labor through more efficient modalities, which engenders the same sort of disillusionment and a general lack of purpose tragically common today:

To those who sweat for their daily bread leisure is a longed-for sweet – until they get it. To those who sweat for their daily bread leisure is a longed-for sweet – until they get it.

He offers this poetic illustration:

There is the traditional epitaph written for herself by the old charwoman:– There is the traditional epitaph written for herself by the old charwoman:–

Don't mourn for me, friends, don't weep for me never,

For I'm going to do nothing for ever and ever.

This was her heaven. Like others who look forward to leisure, she conceived how nice it would be to spend her time listening-in-for there was another couplet which occurred in her poem:–

With psalms and sweet music the heavens'll be ringing,

But I shall have nothing to do with the singing.

Yet it will only be for those who have to do with the singing that life will be tolerable and how few of us can sing!

Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well. Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.

The strenuous purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of economic abundance. But it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.

Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy. It is a fearful problem for the ordinary person, with no special talents, to occupy himself, especially if he no longer has roots in the soil or in custom or in the beloved conventions of a traditional society. To judge from the behaviour and the achievements of the wealthy classes to-day in any quarter of the world, the outlook is very depressing! For these are, so to speak, our advance guard – those who are spying out the promised land for the rest of us and pitching their camp there. For they have most of them failed disastrously, so it seems to me – those who have an independent income but no associations or duties or ties – to solve the problem which has been set them.

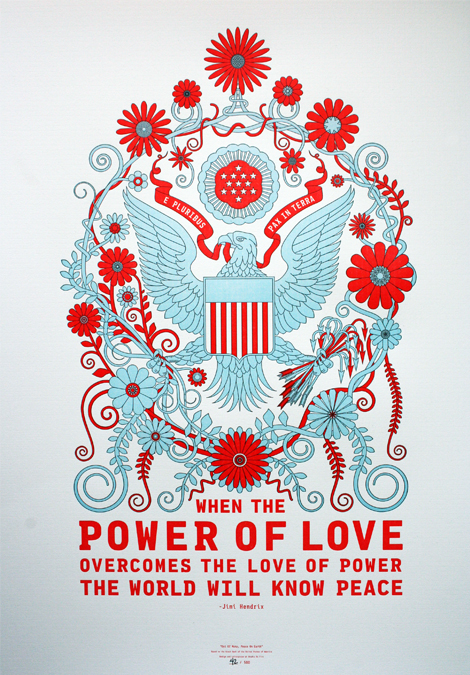

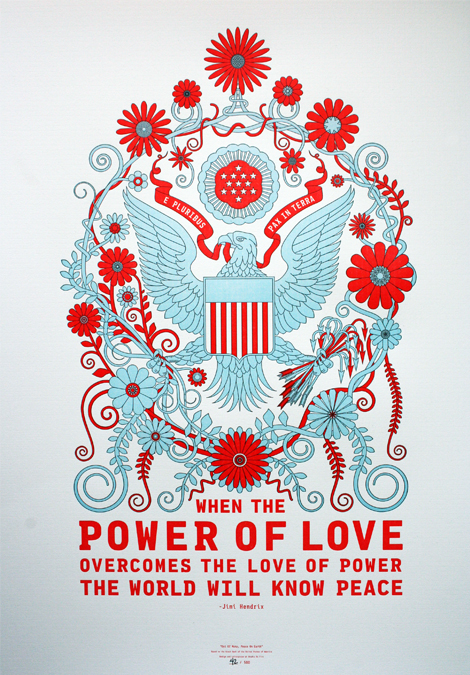

Turning his gaze to the shifting value-system behind money-making, he presages the words of Jimi Hendrix:

There are changes in other spheres too which we must expect to come. When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues. We shall be able to afford to dare to assess the money-motive at its true value. The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease. All kinds of social customs and economic practices, affecting the distribution of wealth and of economic rewards and penalties, which we now maintain at all costs, however distasteful and unjust they may be in themselves, because they are tremendously useful in promoting the accumulation of capital, we shall then be free, at last, to discard. There are changes in other spheres too which we must expect to come. When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues. We shall be able to afford to dare to assess the money-motive at its true value. The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease. All kinds of social customs and economic practices, affecting the distribution of wealth and of economic rewards and penalties, which we now maintain at all costs, however distasteful and unjust they may be in themselves, because they are tremendously useful in promoting the accumulation of capital, we shall then be free, at last, to discard.

Keynes envisions a value shift from the "useful" to the "good":

We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin. We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin.

He concludes by proposing four factors that would make this vision a reality, which ring all the more presciently true today, and circles right back to the essential lubricant, purpose:

The pace at which we can reach our destination of economic bliss will be governed by four things – our power to control population, our determination to avoid wars and civil dissensions, our willingness to entrust to science the direction of those matters which are properly the concern of science, and the rate of accumulation as fixed by the margin between our production and our consumption; of which the last will easily look after itself, given the first three. The pace at which we can reach our destination of economic bliss will be governed by four things – our power to control population, our determination to avoid wars and civil dissensions, our willingness to entrust to science the direction of those matters which are properly the concern of science, and the rate of accumulation as fixed by the margin between our production and our consumption; of which the last will easily look after itself, given the first three.

Meanwhile there will be no harm in making mild preparations for our destiny, in encouraging, and experimenting in, the arts of life as well as the activities of purpose.

|

|

|

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment